7 Mind-Expanding Facts about Psychedelic History

by Eden Woodruff and Tom Hatsis

The study of psychedelic1Here, we refer to the literal definition of “psychedelic,” which is derived from two Greek words (psyche and delein) and means “mind manifesting.” When we use the word throughout this essay, we do not mean to wrap it up with late 1960s, tie-dye, Sergeant Pepper language, but rather as a general term meaning to use psychoactive plants and fungi to tap into alternative forms of consciousness. history can be as rich and mind-expanding as the substances themselves—full of odd moments and ironies that challenge our current paradigms around the entheogenic experience. In this article, we hope to demonstrate that psychedelic history, and its relevant characters, is highly complex.

Here are 7 overlooked facts that enrich our understanding of psychedelic history:

1. The Mazatec healer, María Sabina, saw no difference between synthetic psilocybin and natural mushrooms

As the psychedelic community makes efforts to gain public acceptance of psilocybin as a therapeutic medicine, many have voiced concern about maintaining the purity of the mushroom.

At the Spirit Plant Medicine Conference, 2018, one speaker addressed the idea of synthetic psilocybin corrupting the central essence of the natural fungal medicine, once the former goes mainstream. The audience showed much support for this sentiment.

But how true is it? Will laboratory grown psilocybin compromise the mushroom experience’s integrity?

Mazatec curandera María Sabina, who first gave Robert Gordon Wasson and his travel-partner Allen Richardson psilocybin mushrooms in 1955, didn’t think so. In 1962 R. Gordon Wasson returned to visit María Sabina. This time, he invited Anita and Albert Hofmann along for the journey. Albert brought a few bottles of synthetic mushroom pills (PS-39) grown in Sandoz Laboratories.

When it came time for the Velada (mushroom ceremony), Hofmann suggested that Sabina use his synthetic pills instead of the natural mushrooms. Sabina obliged. After the Velada, Hofmann reported that Sabina claimed “that the pills had the same power as the mushrooms, that there was no difference.”

Hofmann even left Sabina with a gift: a vial of his mushroom pills. María Sabina accepted the gift with gratitude, noting that she could now hold sessions for people during the off-season, when the mushrooms didn’t grow.2Albert Hofmann, LSD: My Problem Child: Reflections on Sacred Drugs, Mysticism and Science (CA: MAPS, 2009), 152.

One new insight into psychedelia, popularized by Dr. Rick Strassman, is the idea that perhaps it is not the plant itself that is spiritual, but rather the molecule within the medicine, whether natural or synthetic, that is spiritual.

2. Christians once had entheogenic traditions

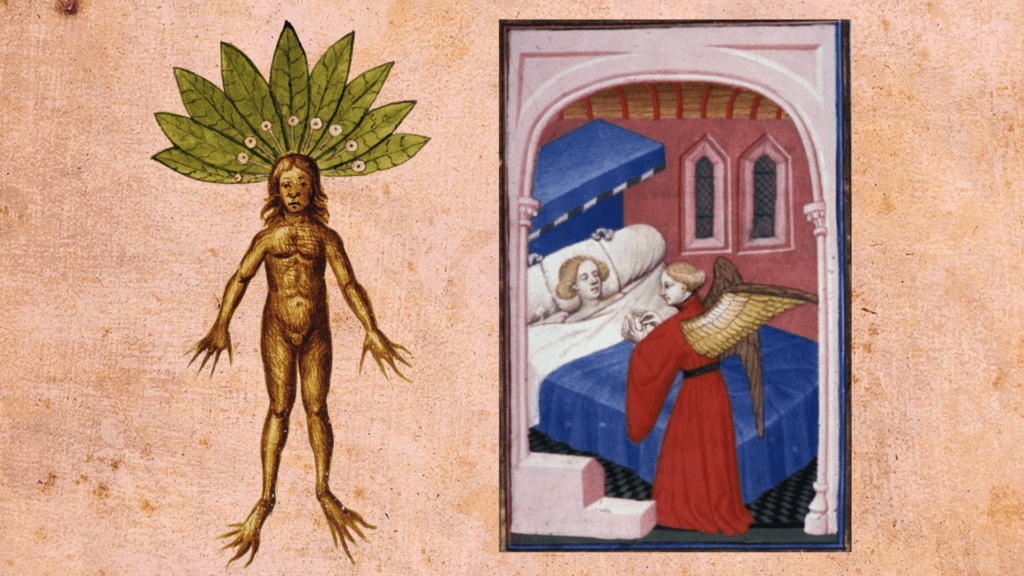

Today we see hard lines drawn between Christianity and entheogenic experiences. But in the early days of the faith and up until the temperance movement, various Christians often incorporated psychedelics into their spiritual practices. In fact, substance use was encouraged by Church leaders so that one may access the godhead.

For example, the first great Christian apologist, Origen (d. 254 CE), recommended drinking mandrake potions to achieve solace with the Christian God. This act, Thomas of Perseigne (d. 1190) references as “the Good Sleep of the Eternal.”3Christian Ratsch, Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants (VT: Park Street Press, 2005), 355.

Additionally, the 3rd century Syrian bishop Theodorat enjoyed taking opium (in drink or smoke – we do not know), and then reading from the gospels. It seems as if, so long as a Christian was not using a psychedelic to practice an opposing faith from standard orthodoxy (i.e., heresy), the authorities paid no mind. Christian entheogenic abstinence is a modern invention — no older than about 175 years.

3. Unknown entheogens of the ancient world

There are a few substances written about in ancient records that we have yet to identify.

Pliny tells us in his Natural History of “the thalassægle,” that can be taken in drink and “presents to the fancy visions of a most extraordinary nature.” There was also the Persian psyche-magical plant, hestiatoris, a recreational plant which causes “gaiety and good fellowship at carousals”.4Pliny, Natural History Bk 24, Chap. 102.

Historians have no idea what thalassægle or hestiatoris were. They could have been local names for known psychoactive plants or fungi (i.e., cannabis or a psilocybe mushroom or anything really) or they could be psychoactive plants and fungi we have yet to identify.

Perhaps most intriguing is a passage from Plutarch, a first century CE philosopher and priest to the Oracles of Delphi. Plutarch refers to the Maenads (the female worshipers of Dionysus) and their use of ivy to achieve enthousiasmós (the ancient Greek word from which Carl Ruck derived the word “entheogen”5Meaning “to generate divinity within”.).

Plutarch’s description clearly points towards an entheogenic plant when he writes that the ivy causes a “wineless drunkenness and joyousness” in those who consume it; and yet, we know of no kind of ivy today that would cause such effects.

Could it be that the ancient Greeks over-harvested the ivy to the point of extinction? Or perhaps “ivy” could have been a local name for a plant like opium or mandrake (much the same way some people refer to cannabis as “weed” today). It’s enough to make one wonder what other substances have been lost to us through the uncompromising ruins of time for one reason or another6Plutarch, Roman Questions, 112.5–6.17..

4. LSD was once used for gay conversion therapy

Much has changed in the West. During the 1950s, homosexuality was seen as a brain disorder, no different from schizophrenia or mania. As such, doctors working with LSD to cure all sorts of mental disorders used that chemical as a tool for gay conversion therapy.

Heading up this area of study was Dr. Joyce Martin at the Marlborough Day Hospital in England. She gave LSD to a number of closeted homosexual volunteers hoping to turn them straight.

Because gays suffered from depression and anxiety due to the more conservative times they lived in, Dr. Martin saw LSD-induced conversion therapy as a compassionate alternative.7See Joyce Martin, “The Treatment of Twelve Male Homosexuals with ‘L.S.D.’” in Acta Psychotherapy, 10 (1962); Joyce Martin, “A Case of Psychopathic Personality with Homosexuality Treated by LSD,” in Richard Crocket and Sandison, Ronald (eds.), Hallucinogenic Drugs and their Psychotherapeutic Use: Proceedings of the Quarterly Meeting of the Royal Medico-Psychological Association (London, February, 1961).

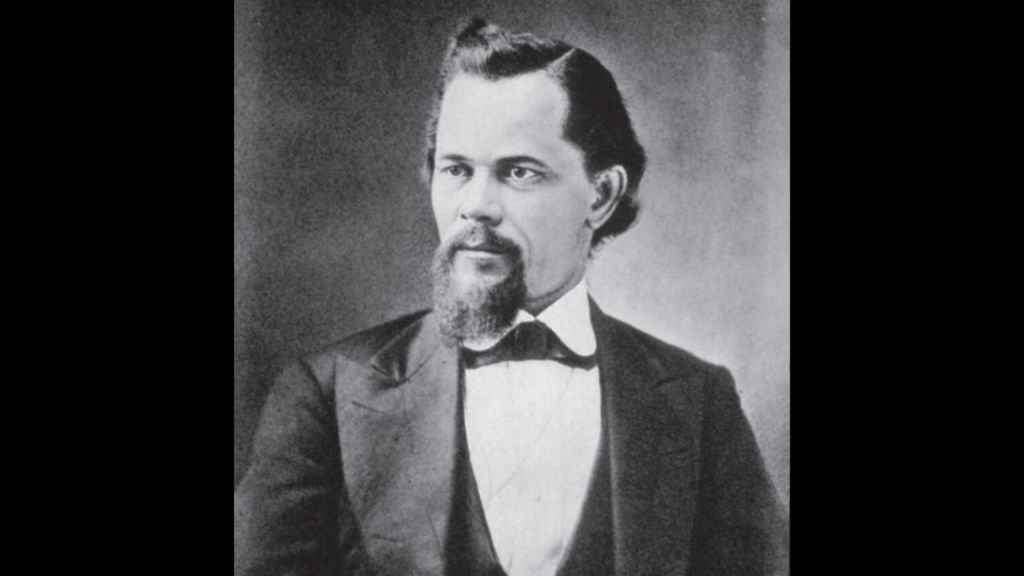

5. One of the most famous Victorian psychedelic magicians was a black man, Paschal Beverly Randolph

Randolph began his psyche-magical career in his twenties, mixing various potions consisting of opium and Solanaceous plants like henbane and belladonna. In 1855, at age 30, Randolph traveled to Paris where he fell in with the famous Club de Hashichins, a group of poets and artists who met regularly at the Hôtel de Pimodan to sample dawamesk, a cannabis-based paste supplied by Dr. Jacques-Joseph Moreau de Tours.

Moreau de Tours had hoped to use dawamesk to prove the existence of the soul and its ability to detach from the body and enter spiritual realms. After engaging in these experiments with Moreau de Tours, Randolph dubbed hashish as “the medicine of immortality.”

He would use hash as an aid in such magical techniques as scrying, captromancy (generating apparitions in mirrors), and astral projection. He also started to add cannabis to his opium/Solanaceae potions in heavy doses. The following magical ointment recipe has a staggering amount of psychoactive ingredients: 50 grams of henbane, 20 grams of belladonna, 250 grams of opium, and 300 grams of hashish!

This salve, used correctly, would bring a person’s “soul through the shadow, into regions of ineffable light, and glorious, illimitable, transcendent beauty.”

Randolph later created “The Ansairetic Mystery,” a powerful ritual of sex and psychedelics that placed women on equal footing with men—a novel concept in the late 1800s.8Chris Bennett, Liber 420: Cannabis, Magickal Herbs, and the Occult (Trine Day, 2018), 401 ff. For “Ansairetic Mystery” see Thomas Hatsis, Psychedelic Mystery Traditions: Spirit Plants, Magical Practices, Ecstatic States (VT: Park Street Press, 2018), 225-28.

6. Until the modern day, wine was considered an entheogen

Due to the dastardly temperance movement and the pitiful, embarrassment to civilization that is the failed “War on Drugs,” we today set a hard line between “drugs” and “alcohol.”

But in the ancient, medieval, and Victorian worlds alcohol was an entheogen. Ideas like “addiction” and “alcoholism” (as we think about them) did not exist until modern day. The wine drunk by followers of Dionysus was seen as every bit entheogenic as a psilocybin mushroom.

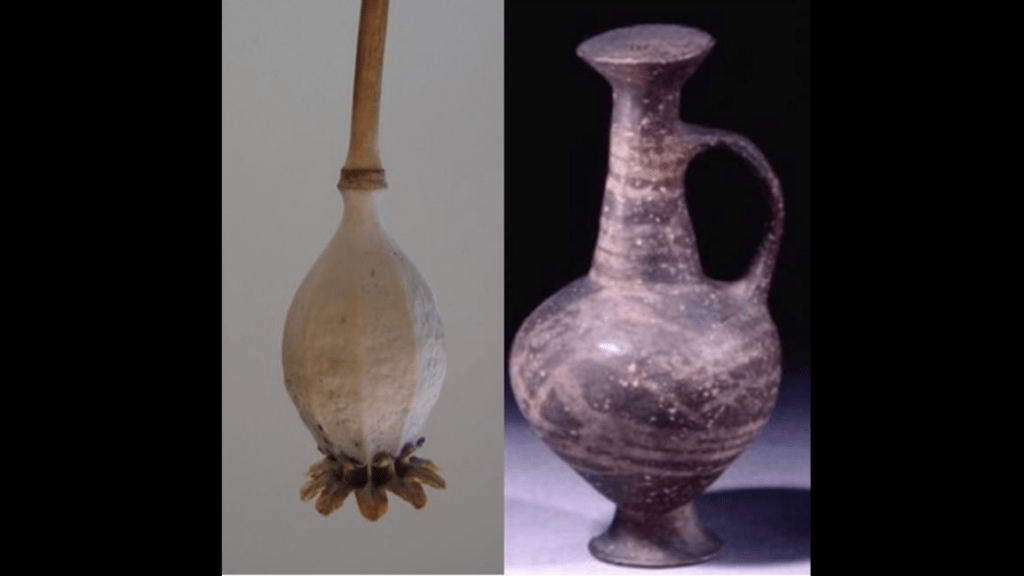

A couple examples: a “strong cup of Avicenna” (the 11th century Islamic physician) referred to an opium-based wine. Additionally, the ancient Greeks often shaped their amphorae (vessels used to hold a liquid) to look like whatever substance was added to the alcohol (e.g., archeologists have uncovered opium-shaped jugs).

Wine in the ancient world rarely registered at more than 14% alcohol, so plant and fungal matter was added to strengthen it9Carl Ruck, “The Wild and the Cultivated: Wine in Euripides’ Bacchae,”in Wasson et al., Persephone’s Quest: Entheogens and the Origins of Religion (CT: Yale University Press, 1986), 179-223. Dionysian worship centered around wine; though, psychoactive plants and fungi might have been added to strengthen the effects (one hydria found in a Thracian graveyard seems to depict a couple adding a mushroom to their wine10Carl Ruck and Mark Hoffman, “Coda: A Flower of a Different Sort,” in Carl Ruck (ed.), Dionysus in Thrace (CA: Regent Press), 259.).

7. Ancient psychedelia was hardly countercultural

A couple of years ago Eric Dolan wrote an article for PsyPost titled Psychedelic mushrooms reduce authoritarianism and boost nature relatedness, experimental study suggests. Not three days later, Philip Smith released his more direct article, Magic Mushrooms Fight Authoritarianism.

Some might take this to mean that psychedelic use in general always leads to an antiauthoritarian perspective. But this doesn’t seem to have always been the case throughout history. In the days of the ancient Mediterranean, the rites of the gods and statewide celebrations often went hand in hand.

Take the Feast of Hathor, celebrated throughout Dendera, Egypt. During this festival, which took place in the month of Thoth (our September 17th), celebrants drank highly psychoactive mandrake beer, grown on the island of Elephantine11John Riddle, Goddesses, Elixirs, and Witches: Plants and Sexuality Throughout Human History (NY: Palgrave MacMillan, 2010),59.. This kind of psychedelic experience served to strengthen, not loosen, the peoples’ allegiance to society.

There were also the burial rites of the Scythians when a neighbor died. According to the first Western Historian, Herodotus, after the body had been placed in the ground, the Scythians would construct a tarp-shelter and burn cannabis inside, falling into ecstasy for their fallen comrade12Herodotus, Histories, Bk 4, Chap. 75..

This ancient pagan rite was hardly anti-status quo. It served to unify the people.

Conclusion

Mind-manifesting experiences took many forms and changed throughout time, always culturally bound to the people having them, whether in ancient Greece or Edwardian England. We tend to dose all history with our own modern ideas, constantly shaping the people of the past into more easily digestible characters and scenarios. But our forerunners were as deep and complicated as we are today. And while we often paint the past with the palette of the present, to do so is to overlook the brilliant strangeness of our ancestry.